I. Introduction: Setting the Stage

The real estate investment landscape offers diverse vehicles for capital deployment, each with unique structures, strategies, and return profiles. Among these, Private Real Estate Equity Funds (PERE Funds) and Publicly-Listed Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) represent two prominent avenues for accessing real estate assets. Understanding their fundamental differences is paramount for investors seeking to align their capital with appropriate risk-return objectives.

Brief Overview

Private Real Estate Equity Funds (PERE Funds) are typically structured as pooled investment vehicles, often limited partnerships, that acquire, manage, and dispose of private real estate assets. These funds raise capital from a select group of investors, including high-net-worth individuals and institutional entities. NAIOP describes a real estate private equity fund in its simplest form as a partnership established to raise equity for ongoing real estate investment. They are generally characterized by a finite lifespan and a focus on capital appreciation over a defined investment horizon.

Publicly-Listed Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs), conversely, are companies that own, operate, or finance income-producing real estate across various property sectors. Their shares are traded on public stock exchanges, offering liquidity to investors. REIT.com explains that REITs are modeled after mutual funds and historically provide investors with regular income streams, diversification, and long-term capital appreciation. They are typically structured as perpetual life entities.

The Core Question

This report delves into a critical aspect of real estate investment analysis: how initial financial strategies and acquisition-related costs differentially impact the key performance metrics of PERE Funds compared to publicly-listed REITs. We aim to dissect the early-stage financial decisions and cost structures inherent to each vehicle and trace their influence on eventual investment outcomes.

Importance for Investors

A clear comprehension of these differences is crucial for investors. It informs decision-making by highlighting how upfront costs can erode returns, how strategic choices shape risk exposure, and what realistic performance expectations should be. For instance, the fee structure in PERE funds can significantly affect net returns, while the capitalization of acquisition costs in REITs has different implications for their financial statements and valuation metrics. Ultimately, this understanding empowers investors to better assess the suitability of PERE Funds versus REITs for their specific financial goals, risk tolerance, and investment timelines.

II. Foundational Differences: PERE Funds and REITs at a Glance

Fundamental Structure & Investment Horizon

PERE Funds are typically structured as closed-end funds with a finite life, often ranging from 5 to 10 years, though sometimes longer. The primary investment objective is often capital appreciation, realized upon the sale of assets, with a strong emphasis on achieving a target Internal Rate of Return (IRR). Investopedia notes that PERE fund structures historically follow a framework including investment horizons laid out in a limited partnership agreement (LPA). Liquidity is generally low, as investor capital is locked in for the fund’s duration. FNRP highlights that private equity real estate funds are one of two common deal structures used by private equity firms investing in real estate.

REITs, on the other hand, are generally perpetual life entities, similar to other publicly traded corporations. Their focus tends to be on generating stable income, primarily distributed to shareholders as dividends, coupled with long-term capital appreciation. Investopedia explains that REITs allow investors to earn income from real estate without direct property management. Being publicly traded, REIT shares offer high liquidity. REIT.com emphasizes their historical delivery of competitive total returns through high, steady dividend income and long-term capital appreciation.

Capital Formation Mechanisms

PERE Funds raise capital from a limited pool of investors, typically high-net-worth individuals and institutional investors such as pension funds and endowments, through private placements. NAIOP states that a real estate private equity fund is a partnership established to raise equity. Capital is committed by investors upfront but is usually “called” by the fund manager as investment opportunities are identified and executed. Investment Law Group points out that forming a private real estate fund allows developers to access a dedicated pool of capital without deal-by-deal fundraising.

REITs access capital through public markets. This includes initial public offerings (IPOs) to become publicly listed, followed by secondary equity offerings (issuing more shares) and debt offerings (issuing bonds or securing loans) to fund growth and acquisitions. Nareit reported that U.S. REITs raised $12.2 billion from secondary debt and equity offerings in Q1 2025, illustrating their continuous access to capital markets.

III. Initial Financial Strategies: Divergent Paths to Value Creation

The initial financial strategies adopted by PERE Funds and REITs are fundamentally shaped by their structures, investor expectations, and regulatory environments. These strategies dictate how capital is deployed at the outset and set the stage for future performance.

A. Private Real Estate Equity Funds: Strategy-Driven Capital Deployment

PERE funds are known for their targeted investment strategies, each carrying distinct implications for initial capital allocation and risk-return profiles.

Key Strategies & Their Implications for Initial Investment:

- Core: This strategy focuses on acquiring low-risk, stable, income-producing properties in prime locations. These assets are typically well-maintained and fully leased to creditworthy tenants. SmartAsset describes core investments as prioritizing capital preservation and steady cash flow.Initial Capital Focus: The majority of capital is allocated to the property acquisition cost itself, with relatively lower reserves earmarked for capital expenditures or renovations, as these properties require minimal initial improvements. Origin Investments notes a core property requires very little asset management.

- Core-Plus: Building on the stability of core, this strategy incorporates properties that offer slightly higher return potential through moderate risk enhancements. These properties might be in good locations but may require some level of improvement or active management. SmartAsset indicates Core-Plus involves slightly higher risk for potentially greater returns.Initial Capital Focus: Capital is directed towards the acquisition cost plus a moderate budget for light renovations, cosmetic upgrades, or operational improvements aimed at optimizing income potential.

- Value-Add: This strategy involves acquiring properties that require significant improvements, repositioning, or an operational overhaul to increase their value. These properties often suffer from underperformance due to factors like poor management, outdated facilities, or high vacancy rates. According to SmartAsset, value-add investors aim to enhance property value through strategic renovations and improved management.Initial Capital Focus: A substantial portion of the initial capital is allocated not only to the acquisition cost but also to a significant budget for renovations, redevelopment, and potentially covering operating shortfalls during the stabilization period.

- Opportunistic: Representing the highest risk/return spectrum, opportunistic strategies often target development projects, distressed assets, land entitlement, or niche property types. These investments are typically more speculative and complex. SmartAsset characterizes opportunistic investing as the most speculative, targeting distressed properties or development projects.Initial Capital Focus: While the acquisition cost for a distressed asset might be lower, significant capital is required for development, extensive redevelopment, carrying costs during a longer lease-up or construction phase, and navigating potential complexities.

Leverage Approach:

The use of leverage (debt) in PERE funds varies significantly by strategy. Core funds might use lower leverage (e.g., 40-45% loan-to-value (LTV) as per Origin Investments for core properties) to maintain a lower risk profile, while value-add and opportunistic funds may employ higher leverage to amplify returns, which also increases risk. The initial leverage decision directly impacts the amount of equity capital required from investors for acquisitions.

Capital Call Structure:

The chosen investment strategy influences the timing and magnitude of capital calls. Core funds might call a larger portion of capital upfront for acquisitions. Value-add and opportunistic funds may have phased capital calls, with initial calls for acquisition and subsequent calls for renovation or development milestones. This strategy aims to minimize idle capital and optimize the fund’s IRR.

B. Publicly-Listed REITs: Portfolio-Level Strategic Positioning

REITs typically adopt broader, portfolio-level strategies, often defined by property sector, geography, and their orientation towards growth or income.

Key Strategic Orientations & Their Implications for Initial Investment:

- Property Sector Focus: Many REITs specialize in specific property types, such as office, retail, industrial, residential, healthcare, data centers, or self-storage. Investopedia outlines various types of REITs based on their property sector investments.Initial Capital Focus: Acquisitions are concentrated within the chosen sector. Some REITs may also engage in development projects specific to their sector expertise.

- Geographic Focus: REITs may diversify their portfolios across multiple regions or countries, or they might concentrate their investments in specific high-growth or supply-constrained markets.Initial Capital Focus: Capital is deployed for acquisitions that align with the REIT’s defined geographic footprint or expansion plans.

- Growth vs. Income Orientation:

- Growth-Oriented: These REITs emphasize development, redevelopment, and acquiring properties with significant appreciation potential. They may reinvest a larger portion of their cash flow, potentially leading to lower initial dividend yields but higher long-term FFO and NAV growth.Initial Capital Focus: Higher allocation towards development projects and properties requiring capital expenditure for repositioning.

- Income-Oriented: These REITs focus on acquiring and managing stable, high-occupancy properties that generate consistent and predictable cash flow to support regular and potentially higher dividend payouts.Initial Capital Focus: Primarily on acquiring stabilized, income-producing assets.

Capital Recycling:

A common ongoing strategy for REITs is capital recycling. This involves selling mature or non-core assets and reinvesting the proceeds into new acquisitions or development projects that offer better growth prospects or align more closely with the current strategy. While more of an ongoing activity, the initial portfolio composition may be influenced by assets identified for future recycling.

Balance Sheet Management:

REITs establish initial leverage targets (e.g., debt-to-total assets or debt-to-EBITDA ratios) and actively manage their balance sheets on an ongoing basis. Initial acquisitions are financed through a combination of equity raised from public offerings and debt, adhering to these leverage policies to maintain credit ratings and financial flexibility.

C. Comparative Overview:

PERE funds generally possess greater flexibility to pursue aggressive value-add or opportunistic strategies from their inception, driven by the pursuit of higher IRRs over a defined term and catering to investors with a higher risk appetite. Their private nature allows for more concentrated bets and complex repositioning efforts without the constant scrutiny of public markets.

REITs, due to their public listing, continuous disclosure requirements, and the imperative to pay consistent dividends, often lean towards more stable, income-producing assets, especially in their initial phases or for a significant portion of their portfolio. Growth for REITs is frequently pursued through a disciplined program of ongoing acquisitions and development projects, funded by their access to public equity and debt markets, rather than a single, large-scale opportunistic fund deployment.

IV. Acquisition Costs & Initial Capital Deployment: A Detailed Breakdown

The costs associated with acquiring real estate assets and the way initial capital is deployed significantly differ between PERE Funds and REITs, impacting net invested capital and, consequently, performance metrics.

A. Private Real Estate Equity Funds

PERE funds have a distinct set of fees and costs that directly affect the initial investment amount available for property acquisition and development.

Typical Fee Structures Impacting Initial Investment:

Investors in PERE funds typically encounter several layers of fees, as detailed in offering documents:

- Acquisition Fee: This fee is charged by the fund sponsor (General Partner) to cover the costs and efforts of sourcing, underwriting, diligencing, and closing on an asset. Birgo Capital states that acquisition fees generally range from 0.5% to 3% of the purchase price and are paid at closing. Origin Investments notes this fee is usually between 1% and 2% of the total deal size, often on a sliding scale.

- Fund Formation / Administrative Fee: An upfront fee, often a percentage of committed capital (e.g., 0.25% to 1% as per Birgo Capital), intended to cover the legal, accounting, and administrative expenses associated with establishing the fund and sourcing initial capital.

- Committed Capital Fee (or Asset Management Fee on Committed Capital): Some funds may charge an asset management fee based on committed capital, which can start accruing from the first closing, even before all capital is deployed. Origin Investments mentions this fee typically ranges from 1% to 2% on committed equity for called capital funds. This can create a drag on early returns if deployment is slow.

Non-Fee Acquisition Costs (Hard & Soft Costs):

Beyond sponsor fees, numerous third-party costs are incurred during an acquisition:

- Due Diligence Costs: Expenses for market studies, physical inspections, financial audits of the property, and comprehensive legal reviews.

- Legal Fees: Costs for legal counsel related to transaction structuring, negotiation of purchase agreements, and closing.

- Financing Fees & Costs: If debt is used, these include loan origination fees (which Birgo Capital suggests can range from 0.25% to 2% of the loan amount), appraisal fees, survey costs, environmental assessments (Phase I/II ESA), and title insurance premiums.

- Property-Level Closing Costs: These include transfer taxes, recording fees, and other miscellaneous closing adjustments.

Collectively, these non-fee costs can add several percentage points to the total acquisition cost, further reducing the net capital deployed directly into the income-producing aspects of the asset.

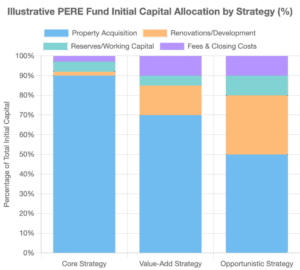

Initial Capital Deployment Allocation (Illustrative):

The allocation of initial capital in a PERE fund is heavily dependent on its strategy. For example:

- Property Purchase Price: This is invariably the largest component.

- Immediate Renovations/CapEx: For Value-Add or Opportunistic strategies, this can be a substantial portion, potentially ranging from 10% to over 30% of the purchase price. Core strategies would have minimal allocation here.

- Operating Reserves/Working Capital: Funds set aside capital to cover initial operating deficits, tenant improvements, leasing commissions, and other contingencies, especially during stabilization periods for Value-Add/Opportunistic projects.

- Closing Costs & Fees: As detailed above, these reduce the capital directly invested into the physical asset or its improvements.

The exact percentages vary widely. For instance, a Core fund might allocate 90% to purchase price and 10% to reserves and closing costs, while an Opportunistic development fund might allocate 40% to land acquisition, 50% to construction, and 10% to soft costs, fees, and reserves. (While a Morgan Stanley guide on private investments was referenced as a potential source for such data, its content was not fetched; however, industry knowledge supports these illustrative allocations).

Chart data is illustrative and based on typical strategic allocations.

B. Publicly-Listed REITs

REITs also incur acquisition costs, but their accounting treatment and the way they are funded differ from PERE funds.

Acquisition-Related Costs (Often Capitalized):

When a REIT acquires a property, direct acquisition-related costs are generally capitalized as part of the property’s cost basis on the balance sheet, in accordance with accounting standards like ASC 805 (Business Combinations). EisnerAmper discusses the accounting for acquisitions, distinguishing between asset acquisitions and business combinations under ASC 805. Rentastic.io also notes that costs like price tag and lawyer fees are logged as assets. These costs include:

- Due diligence expenses

- Legal fees for the transaction

- Appraisal costs

- Environmental assessment costs

- Title insurance

- Transfer taxes and other direct closing costs

By capitalizing these costs, they become part of the depreciable asset base rather than being expensed immediately, which impacts net income differently than if they were expensed.

Impact of SEC Regulations on Acquisitions:

Public REITs are subject to SEC regulations that can add complexity and cost to acquisitions. Specifically, SEC Regulation S-X, Rules 3-14 (for real estate operations) and 3-05 (for business acquisitions), require audited historical financial statements for significant acquired properties or businesses. Cohen & Company explains that S-X 3-14 provides special instructions for audited financials of acquired real estate operations. Goodwin Law highlights that Rule 3-14 is typically more relevant for REITs and failure to timely file can have serious consequences. Compliance with these rules involves significant accounting and auditing efforts, adding to the overall cost and potentially impacting the speed of acquisition integration.

Capital Raising Costs (Indirect Impact on Net Investment):

When REITs raise capital through public equity or debt offerings, they incur underwriting fees, legal fees, and other issuance costs. These costs reduce the net proceeds received by the REIT, meaning that for every dollar of gross capital raised, a smaller amount is available for actual investment in properties or development. These costs are typically netted against the proceeds of the offering in the equity section of the balance sheet or amortized over the life of debt.

Initial Capital Deployment:

REITs deploy capital primarily into acquiring income-producing properties or funding development and redevelopment projects consistent with their stated strategy. The “fee load” on an investor buying REIT shares in the secondary market is typically just brokerage commissions. However, the REIT entity itself incurs the acquisition and capital raising costs mentioned above. These costs are embedded in the REIT’s financial structure and asset base, rather than being explicit fees paid by the shareholder directly upon investment in the same way as PERE fund fees.

C. Comparative Analysis of Acquisition Costs & Deployment:

- Transparency of Costs: PERE fund fees are explicitly detailed in the Limited Partnership Agreement (LPA) and capital call notices. REIT acquisition costs, while disclosed in financial statements (often in footnotes or as part of capitalized asset values), are less directly visible to the average shareholder as a distinct “load” on their share purchase.

- Upfront “Load”: PERE funds often present a higher visible upfront “load” on invested capital due to explicit acquisition fees, fund formation fees, etc. FNRPUSA.com mentions that REITs can have a high front-end “load” in fees (5%-10% of initial investment), though this may refer more to non-traded REITs or initial offering costs rather than ongoing acquisitions by publicly-listed REITs where costs are capitalized. For publicly traded REITs, the “load” for an investor buying shares is the brokerage commission, while the REIT entity bears the acquisition costs internally.

- Speed of Deployment: PERE funds deploy capital as it is called from investors, which can sometimes lead to “cash drag” if deployment is slow. REITs can deploy capital more rapidly if they have recently completed a successful offering and have cash on hand. However, the due diligence and financial reporting requirements under SEC Rules 3-14/3-05 for significant acquisitions can sometimes slow down the closing and integration process for REITs.

V. Key Performance Metrics: Gauging Success

The metrics used to evaluate the performance of PERE Funds and REITs reflect their differing structures, investment objectives, and investor expectations.

A. Private Real Estate Equity Funds:

PERE fund performance is typically assessed using metrics that capture total return over the fund’s life, considering the timing of cash flows and the ultimate return of capital.

- Internal Rate of Return (IRR): This is a primary metric for PERE funds. It represents the discount rate at which the net present value of all cash flows (initial investment, operating cash flows, and exit proceeds) equals zero. IRR is heavily influenced by the timing of these cash flows. Forbes highlights IRR as one of the most commonly used real estate investment metrics.

- Equity Multiple (Multiple on Invested Capital – MOIC): This metric measures the total cash returned to investors divided by the total cash invested. It provides a straightforward indication of overall wealth creation, without being as sensitive to timing as IRR. Origin Investments explains that the equity multiple shows an investment’s true impact on wealth.

- Cash-on-Cash Return: Calculated as the annual pre-tax cash flow generated by a property divided by the total cash equity invested in that property. It provides a measure of current income relative to the equity invested.

- Net Operating Income (NOI): This is the property’s income after deducting operating expenses but before debt service and income taxes. It’s a fundamental measure of a property’s profitability.

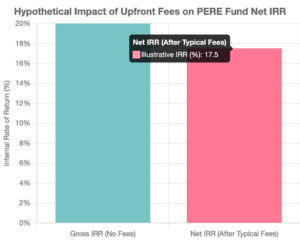

- Gross vs. Net Returns: It is crucial for PERE investors to distinguish between gross returns (at the property or fund level before fees and sponsor promote) and net returns (what the investor actually receives after all fees, expenses, and promote are paid). PrivateEquityList.com clarifies that Gross IRR is before fees, while Net IRR is after fees and costs.

B. Publicly-Listed REITs:

REIT performance metrics focus on operational cash flow, the capacity to pay dividends, the value of underlying assets, and total return to shareholders in the public market.

- Funds From Operations (FFO): A standardized measure of a REIT’s operating performance, widely used by analysts and investors. Nareit defines FFO as net income (computed in accordance with GAAP), excluding gains (or losses) from sales of most property and depreciation and amortization of real estate assets. CIEL Asset Management lists FFO as a key financial metric for REITs.

- Adjusted Funds From Operations (AFFO): Often considered a more accurate measure of a REIT’s recurring cash flow available for distribution as dividends. AFFO typically starts with FFO and adjusts for items like straight-line rent revenue and recurring capital expenditures necessary to maintain properties. TIKR.com includes AFFO among the most important metrics for analyzing REITs.

- Net Asset Value (NAV): An estimate of the market value of a REIT’s total assets minus its total liabilities, usually expressed on a per-share basis. It provides an indication of the underlying value of the REIT’s real estate portfolio. Green Street Advisors’ NAV-based pricing model emphasizes NAV as a starting point for REIT valuation.

- Dividend Yield: The annual dividend per share divided by the REIT’s current market share price. It measures the return an investor receives in the form of dividends.

- Total Shareholder Return (TSR): This combines dividend income and the appreciation (or depreciation) in the REIT’s share price over a specific period, reflecting the total return to an investor.

C. Rationale for Different Metrics:

The divergence in key performance metrics stems from the fundamental differences between PERE funds and REITs:

- PERE Funds: With a finite life and a focus on eventual asset sales, metrics like IRR and Equity Multiple are paramount as they capture the full lifecycle returns, including the exit. Cash-on-Cash return is relevant during the holding period, but the ultimate success is judged by the total capital returned relative to capital invested and the time taken to achieve it.

- REITs: As ongoing operating companies with a perpetual life, REITs are valued based on their ability to generate consistent and growing cash flow to support and increase dividends. FFO and AFFO are critical indicators of this capacity. NAV provides a measure of underlying asset value, while TSR and dividend yield reflect the returns experienced by public market investors.

VI. Core Analysis: Connecting Initial Strategies & Costs to Performance Outcomes

This section dissects how the initial financial strategies and acquisition costs, discussed earlier, directly and indirectly shape the performance metrics for both PERE funds and REITs.

A. Impact on Private Real Estate Equity Funds

Initial Financial Strategy’s Influence on Performance Metrics:

The chosen strategy at a PERE fund’s inception sets clear expectations for risk and return, directly influencing target performance metrics.

- Core Strategy: Typically aims for stable, albeit moderate, IRR and Equity Multiples. Returns are primarily driven by consistent cash flow from well-leased, high-quality properties. The lower risk profile generally translates to lower return targets compared to other strategies. SmartAsset notes core investments focus on consistent income with minimal risk.

- Value-Add Strategy: Involves higher upfront capital for renovations and repositioning. This impacts early cash flows, often resulting in a lower initial Cash-on-Cash return or even a “J-curve” effect where early returns are negative. However, the goal is to achieve higher IRR and Equity Multiples upon stabilization and successful exit, driven by increased NOI and asset value. This strategy carries execution risk – the success of the repositioning plan is critical.

- Opportunistic Strategy: Targets the potentially highest IRR and Equity Multiples. These strategies often involve development, significant redevelopment, or complex situations like distressed assets. They typically exhibit the most pronounced J-curve effect due to long development timelines and substantial upfront capital deployment before income generation. The risk is also the highest, as success depends on factors like successful development, market timing, and navigating complexities.

Acquisition Costs’ Direct Impact on Net Returns:

Acquisition costs, both fees and non-fee related, have a direct and tangible impact on the net returns realized by PERE fund investors.

- Fees (Acquisition, Fund Formation, etc.): These fees directly reduce the amount of investor capital that is actually invested in income-producing assets or increase the total project cost against which returns are measured. For example, if a fund charges a 2% acquisition fee and a 1% fund formation fee on a $10 million equity investment, $300,000 (or 3%) is immediately deducted for fees. This means either only $9.7 million is available to purchase and improve the property, or the investment basis for calculating returns effectively becomes $10.3 million if fees are added to the project cost. This directly lowers the Net IRR and Equity Multiple achievable for the limited partners. As explained by PrivateEquityList.com, Net IRR reflects returns after deducting all fees and costs, making it lower than Gross IRR.

- Non-Fee Costs (Due Diligence, Legal, Financing, Closing): Similar to fees, these costs increase the total investment basis. Every dollar spent on these items is a dollar that doesn’t directly contribute to the property’s income generation or appreciation potential, thereby diluting overall returns.

Chart data is hypothetical, illustrating the general impact of fees.

Capital Call Strategy’s Impact:

The way a PERE fund manager calls capital from investors can significantly influence IRR.

- Timing & Frequency: Qapita notes that calling capital too early can lower IRR because funds sit idle until invested. Conversely, delaying capital calls until an investment is imminent can boost IRR by ensuring capital is deployed quickly into performing assets. However, calling too late might risk missing investment opportunities. Frequent, smaller calls can be administratively burdensome but may optimize IRR if timed well.

- Subscription Lines of Credit: Many PERE funds use subscription lines of credit (or capital call facilities) to bridge the gap between an investment closing and receiving called capital from LPs. This allows funds to close deals quickly. RCLCO suggests that while reasonable for quick execution, extended use of subscription lines can delay investor equity calls, thereby artificially increasing IRR (as the clock on LP capital starts later) and potentially promote payments, even if overall net returns to LPs are not enhanced or are reduced by interest costs.

Initial Leverage Strategy’s Impact:

The level of debt used in initial acquisitions is a powerful driver of PERE fund returns. RCLCO points out that higher leverage can magnify both positive and negative returns. If the property performs well, leverage boosts the Equity Multiple and IRR on the invested equity. However, if the property underperforms, high leverage exacerbates losses and increases the risk of default. The choice of leverage is often tied to the fund’s strategy, with riskier strategies sometimes employing higher leverage to reach target returns.

Initial Diversification Strategy’s Impact:

Diversification across property types, geographic locations, and tenant bases is a common risk mitigation strategy. Primior emphasizes that market diversification protects against local economic downturns. While diversification can lead to more stable and predictable average returns (IRR and Equity Multiple), it might also temper the extreme high returns possible from a successful, highly concentrated bet. Arbour Investments notes that PERE funds pool capital to invest in various projects, implying a degree of diversification within the fund’s strategy. The initial diversification approach sets the stage for the fund’s overall risk-adjusted return profile.

Illiquidity Premium:

A portion of the higher expected returns in PERE funds is often attributed to an “illiquidity premium” – compensation to investors for tying up their capital for an extended period. Trion Properties explains that real estate is considered illiquid, and this premium is the excess return an investor might earn for this lack of liquidity. Effective management of initial strategies and costs is vital to actually realizing this premium net of all expenses.

B. Impact on Publicly-Listed REITs

Initial Financial Strategy’s Influence on Performance Metrics:

A REIT’s initial strategic orientation has a profound effect on its key performance indicators.

- Growth-Oriented Strategy: REITs focusing on growth through development, redevelopment, or acquiring properties with significant upside potential may experience faster FFO and AFFO growth and NAV appreciation over time. However, this strategy might entail higher capital expenditures and potentially lower initial dividend yields if a larger portion of cash flow is reinvested into growth initiatives rather than paid out as dividends.

- Income-Oriented Strategy: REITs prioritizing stable income tend to invest in mature, high-occupancy properties. This typically results in a higher initial dividend yield and more predictable FFO/AFFO. However, the growth rate of these metrics and NAV might be more modest compared to growth-oriented REITs.

- Sector/Geographic Focus: The performance of a specialized REIT is closely tied to the fundamentals of its chosen property sector(s) and geographic market(s). A diversified REIT (across multiple sectors or regions) may exhibit more stable FFO, AFFO, NAV, and dividend yields, as weakness in one area can be offset by strength in another. Housivity.com notes that REITs offer a way to diversify portfolios and gain exposure to real estate.

Acquisition Costs’ Impact (Capitalized vs. Expensed):

The accounting treatment of acquisition costs in REITs influences financial statements and metrics differently than in PERE funds.

- Capitalized Costs: As mentioned, REITs typically capitalize direct acquisition costs, adding them to the property’s basis on the balance sheet. Rentastic.io confirms that acquisition costs are logged as assets. While depreciation (on this higher asset base) is added back when calculating FFO, the increased asset value can influence NAV calculations. A higher capitalized cost base means more depreciation over time, which reduces GAAP net income but is adjusted for in FFO. The Green Street Advisors’ report on REIT valuation indicates NAV is a function of the value of assets owned, which would include capitalized costs.

- SEC Rules (3-14/3-05): The costs associated with complying with SEC Rules 3-14 and 3-05 for significant acquisitions (e.g., audits of acquiree financials) are real expenses for the REIT. These compliance burdens can also delay the deployment of capital and the integration of acquired assets, potentially creating a near-term drag on FFO and AFFO growth until synergies are realized.

Capital Raising Strategy & Costs’ Impact:

How a REIT raises capital and the associated costs have significant implications:

- Equity Offerings: Issuing new shares can be dilutive to FFO per share and AFFO per share in the short term if the proceeds are not deployed quickly into accretive investments (i.e., investments yielding returns higher than the cost of equity). The underwriting fees and other issuance costs also reduce the net proceeds available for investment.

- Debt Offerings: Raising capital through debt increases a REIT’s leverage. While this can enhance FFO/AFFO per share if the return on assets acquired with debt exceeds the cost of debt, it also increases interest expense (reducing net income and FFO/AFFO before interest adjustments) and financial risk. Higher debt levels can also impact dividend coverage ratios.

Initial Leverage Strategy’s Impact:

A REIT’s initial and ongoing leverage strategy is a key determinant of its risk profile and return potential. The Green Street Advisors’ PDF notes that REITs with less leverage have historically delivered better returns and investors often ascribe higher NAV premiums to low-leverage REITs. Higher leverage can amplify FFO/AFFO per share if investments are accretive but also increases the volatility of earnings and the risk to NAV if property values decline. It directly affects the safety and sustainability of dividend payments.

Initial Diversification Strategy’s Impact:

A well-diversified initial portfolio (by property type, geography, tenant concentration, and lease expirations) generally leads to more stable and predictable FFO, AFFO, NAV, and dividend yields. This stability is often attractive to risk-averse public market investors. Nareit’s Investor’s Guide to REITs highlights that REITs can serve as a powerful tool for portfolio diversification, which implies that diversification within a REIT itself contributes to this benefit.

C. Comparative Impact Analysis: PERE vs. REITs

- Sensitivity to Upfront Costs: PERE fund IRR and Equity Multiple are highly sensitive to upfront fees and acquisition costs. These costs directly reduce the net capital invested or increase the investment base against which returns are measured, thus creating a significant hurdle for net returns to LPs. For REITs, FFO, AFFO, and NAV are impacted more by how these costs are accounted for (typically capitalized) and the overall efficiency of capital deployment and operations post-acquisition. The impact on REIT shareholders is less direct from a “fee load” perspective but is reflected in the overall financial health and valuation of the REIT.

- Valuation and Cost Recognition:

- PERE: Costs are effectively netted against investor capital or returns. Valuations are typically based on periodic appraisals or eventual sale prices.

- REITs: Acquisition costs are often capitalized into the asset’s book value. The public market valuation (share price) of a REIT can deviate significantly from its NAV, leading to trading at premiums or discounts. This divergence can be influenced by many factors, including market sentiment, interest rate expectations, and perceived management quality, not just the underlying asset values net of capitalized costs. Nareit has discussed the public-private real estate valuation divergence, where REIT implied cap rates can differ from private appraisal cap rates.

- Impact of Deployment Speed:

- PERE: “Cash drag” from undeployed committed capital (capital called but not yet invested) directly and negatively impacts IRR, as the clock starts on LPs’ capital from the time of the call.

- REITs: Similarly, “cash drag” can occur if a REIT raises a large amount of capital through an equity or debt offering but is slow to deploy it into accretive investments. This can dilute FFO/AFFO per share in the interim.

- Alignment of Interest (Fees vs. Performance):

- PERE: There is ongoing debate in the industry about PERE fund fee structures (e.g., the “2 and 20” model – 2% management fee and 20% carried interest/promote) and whether they always align GP interests with LP interests. Acquisition fees, for example, are often earned by the GP regardless of the ultimate performance of the acquired asset. RCLCO has published commentary on PERE fees, suggesting changes for better alignment.

- REITs: REIT management compensation is often tied to metrics like FFO/AFFO growth, Total Shareholder Return (TSR), and maintaining or growing dividends. Decisions regarding acquisitions, developments, and financing directly impact these metrics, creating a different set of agency considerations.

VII. Long-Term Financial Strategies & Outcomes (Brief Outlook)

The initial financial strategies and cost structures lay the groundwork for long-term outcomes, which also diverge significantly between PERE funds and REITs.

PERE Funds:

For PERE funds, the initial strategy (Core, Value-Add, Opportunistic) fundamentally dictates the pathway towards asset stabilization, potential interim cash distributions, possible refinancing events to return some capital to investors, and the ultimate disposition (sale) of assets. The sale event is the primary driver for realizing the targeted Equity Multiple and the final IRR. Operational expertise demonstrated by the fund manager post-acquisition, in executing the specific business plan for each asset (e.g., leasing, renovation, development), is paramount to achieving the projected returns. The finite life of the fund necessitates a clear exit strategy from the outset.

REITs:

Publicly-listed REITs, being perpetual entities, focus on ongoing active asset management, proactive leasing strategies to maintain high occupancy and rental growth, and optimizing Net Operating Income (NOI) across their portfolio. This operational excellence is key to supporting sustainable FFO/AFFO growth and consistent, ideally growing, dividend payments to shareholders. Strategic acquisitions and dispositions are typically continuous activities aimed at enhancing the overall portfolio quality and growth prospects, rather than being tied to a fixed fund life or a singular exit event for the entire entity. EquityMultiple highlights that REITs’ liquidity means their price can be volatile like other stocks, contrasting with the illiquid nature of private real estate. Concreit notes that real estate funds (which can include private funds) may offer more growth potential through strategic reallocation, while REITs are often favored for steady income.

VIII. Conclusion: Synthesizing Impacts and Investor Considerations

The journey from initial capital deployment to eventual performance outcomes is markedly different for Private Real Estate Equity Funds and Publicly-Listed REITs. Their distinct initial financial strategies and acquisition cost structures are foundational to these divergent paths.

Recap of Key Differentiators:

- Initial Financial Strategies: In PERE funds, strategies are highly project/deal-specific (Core, Value-Add, Opportunistic) and directly correlate with expected risk/return profiles, primarily measured by IRR and Equity Multiple. These are heavily influenced by the upfront fee load and the efficiency of the capital call process. For REITs, initial strategies are more portfolio-level (sector focus, geographic concentration, growth vs. income), shaping ongoing metrics like FFO, AFFO, NAV, and dividend sustainability.

- Acquisition Costs: PERE funds feature explicit upfront fees (acquisition, formation) that directly reduce net invested capital or increase the investment hurdle. REITs typically capitalize acquisition costs, embedding them into the asset base; these costs influence metrics more indirectly through the overall size and financing of the asset portfolio and ongoing depreciation charges (which are then adjusted for FFO).

Key Investor Takeaways

- PERE Investors: Must diligently scrutinize the fund’s fee structure, the manager’s track record in executing the stated strategy (Core, Value-Add, Opportunistic), and understand how initial costs and capital deployment plans (including capital call timing and use of subscription lines) will impact their net returns (Net IRR, Net Equity Multiple). The J-curve effect and illiquidity are key considerations.

- REIT Investors: Should analyze the quality and sustainability of FFO/AFFO, the drivers of NAV (including how acquisitions are valued and integrated), dividend coverage and growth prospects, and the management team’s overall capital allocation strategy (acquisitions, development, leverage, and capital recycling). While acquisition costs are embedded, their prudent management is crucial for long-term value creation and TSR.

Advantages & Disadvantages Stemming from Initial Differences:

- PERE Funds:

- Advantages: Potential for higher returns, often driven by the illiquidity premium and the ability to execute more aggressive value-add or opportunistic strategies; greater manager control over assets.

- Disadvantages: Higher upfront and ongoing fees; lower liquidity (capital typically locked in for 5-10+ years); significant execution risk tied to manager skill; less transparency compared to public companies. (Ref: Concreit mentions higher fees and longer commitment for private funds).

- Publicly-Listed REITs:

- Advantages: Higher liquidity (shares traded on public exchanges); greater transparency due to public reporting requirements; potential for steady and predictable income through dividends; easier access for a broader range of investors with lower minimum investments. (Ref: SmartAsset highlights liquidity and regulatory oversight for public REITs).

- Disadvantages: Returns can be influenced by broader stock market sentiment, potentially leading to share prices detaching from underlying NAV; less flexibility in pursuing highly opportunistic strategies due to dividend requirements and public scrutiny; potential for FFO/share dilution from equity offerings. (Ref: Saint Investment notes REITs are more liquid but private funds may offer lower correlations).

Final Thought:

Ultimately, the choice between investing in Private Real Estate Equity Funds and Publicly-Listed REITs hinges on an investor’s individual financial objectives, risk tolerance, liquidity needs, and desired investment horizon. Both vehicles offer exposure to the real estate asset class, but their initial financial strategies and acquisition cost structures create fundamentally different investment propositions. A thorough understanding of these early-stage factors is indispensable for making informed investment decisions and aligning expectations with the potential realities of each path.