The Dual Challenge: Boosting Home Ownership and Ensuring Investor Profitability in Affordable Housing

Table of Contents

Introduction

Across continents, the dream of home ownership is becoming increasingly distant for millions. What was once a reliable pillar of wealth creation and community stability has transformed into a global economic fault-line. This affordable housing crisis is not a monolithic problem but a complex interplay of economic pressures, supply shortages, and systemic barriers. Aspiring homeowners face a daunting landscape of soaring home prices, sharply rising mortgage rates, and stagnant wages that fail to keep pace with the escalating cost of living (Federal Housing Finance Agency, 2024; Ballard Brief, 2024).

This challenge presents a fundamental tension. On one hand, there is a pressing social imperative to expand access to affordable housing. On the other, the private capital necessary to fund such large-scale development requires viable financial returns. The core problem statement, therefore, is this: How can the real estate and investment sectors deploy innovative strategies to increase affordable home ownership opportunities while maintaining, or even enhancing, financial returns for investors? This is not a question of choosing between social good and profit, but of aligning them.

This report will navigate this complex terrain by first dissecting the primary barriers that make affordable home ownership so elusive. It will then conduct a deep analysis of four innovative investment models—Shared Equity Homeownership, Community Land Trusts, Social Impact Bonds, and Crowdfunding—examining their mechanisms, ownership pathways, and profitability structures. Finally, it will explore the critical role of public-private partnerships and supportive government policies in creating an ecosystem where these innovative solutions can thrive, ultimately charting a course toward a future where home ownership is both accessible and a sound investment.

Understanding the Barriers: Why is Affordable Home Ownership So Elusive?

To devise effective solutions, we must first diagnose the multifaceted nature of the housing affordability crisis. The barriers to home ownership are not singular but are a compounding web of economic, supply-side, and systemic challenges that collectively place the goal out of reach for a growing segment of the population. Any innovative strategy must be designed to navigate and dismantle these specific obstacles.

Economic Pressures on Buyers

The most immediate hurdle for prospective buyers is the sheer financial infeasibility of purchasing a home in the current market. This pressure manifests in several key ways:

- The Affordability Gap: A stark chasm has opened between housing costs and household incomes. In the United States, for example, home prices in 99% of counties are beyond the reach of the average income earner, who makes approximately $71,214 annually (CBS News, 2023). A recent analysis by Forbes highlights that it would now take over 40% of the national median income to afford a median-priced house, a level of unaffordability comparable to the period of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (Forbes, 2024).

- Wage Stagnation vs. Rising Costs: The problem is exacerbated by the long-term trend of wages failing to keep pace with the rising cost of living and, most acutely, housing prices. This dynamic severely curtails the ability of households, particularly younger generations, to save for a down payment and closing costs, which are often the most significant upfront barriers to entry (Ballard Brief, 2024).

- High Interest Rates: Elevated mortgage rates have dramatically increased the long-term cost of borrowing. Rates surpassing 7% in 2024 have added hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars to monthly mortgage payments, effectively pricing many potential buyers out of the market even if they could afford the down payment (EY, 2024).

Supply-Side Constraints

The affordability crisis is not solely a demand-side issue; it is fundamentally rooted in a chronic lack of adequate housing supply, especially at affordable price points.

- Critical Housing Shortage: There is a significant and persistent shortage of housing units across the country. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development estimated a need for 2.5 million additional housing units as far back as 2018 to meet long-term demand, a deficit that has only grown (Habitat for Humanity, 2024). This supply-demand imbalance naturally drives up prices for the limited inventory available (GAO, 2023).

- High Construction & Land Costs: The economics of development are a major deterrent. The rising costs of land, materials, and labor make it financially challenging for developers to construct new homes, particularly for the lower end of the market. As a result, most new construction targets higher price points where profit margins are more secure, further neglecting the need for affordable starter homes (Fusion, 2024; PERE News, 2024).

Systemic & Personal Hurdles

Beyond broad economic trends and supply deficits, a range of systemic and personal barriers lock many out of the housing market.

- Debt and Credit History: Many prospective buyers, especially from younger generations like Gen Z, are burdened with significant existing debt, such as student loans. This, combined with a limited or poor credit history, makes it difficult to qualify for a mortgage, creating a formidable personal barrier to homeownership (hfhcc.org, 2024).

- Restrictive Zoning Regulations: In many communities, local zoning laws present a significant obstacle to increasing housing supply. Regulations that limit housing density, mandate large lot sizes, or prohibit certain types of housing (like multi-unit buildings) make it difficult and costly for developers to build affordable projects at scale (NCSL, 2024; SimmCapital).

Innovative Investment Strategies: Balancing Social Impact and Financial Returns

Addressing the deep-seated barriers to home ownership requires a paradigm shift in how we view housing investment. The solution lies not in philanthropy alone, but in sophisticated financial models that align the goals of social progress with the logic of market returns. This section explores four such innovative strategies that offer a viable path to increasing home ownership while providing attractive, risk-adjusted returns for investors.

Introduction to Impact Investing in Housing

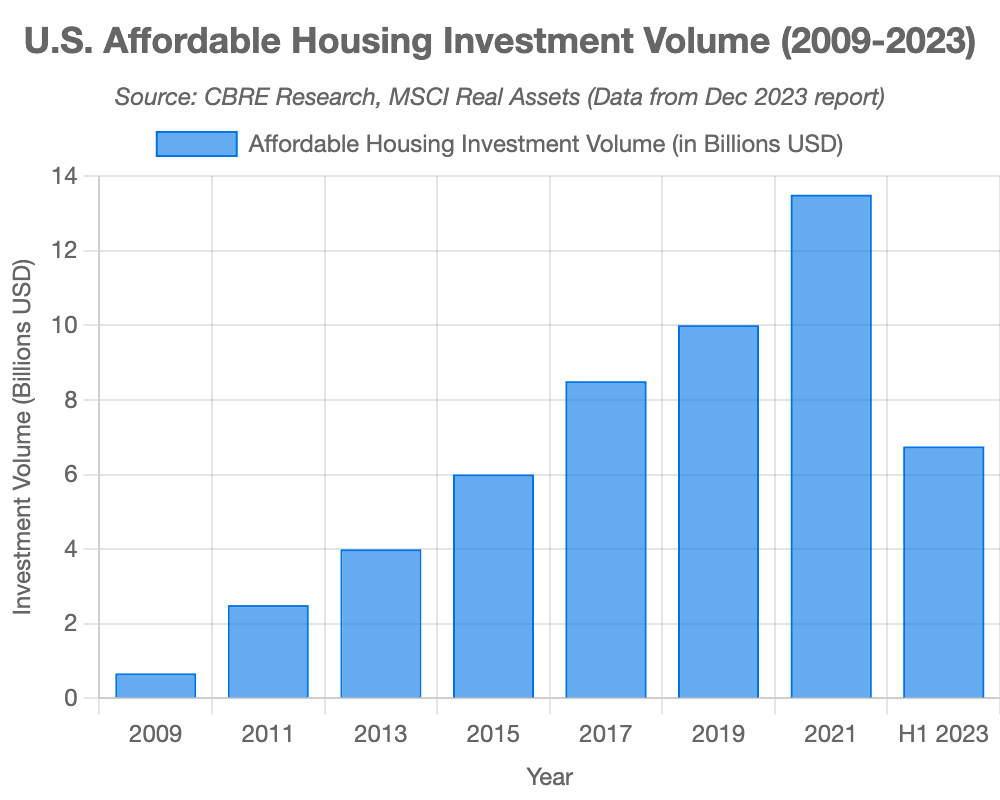

Affordable housing is increasingly recognized as a compelling asset class within the impact investing universe. It offers a “double bottom line” by generating both measurable social benefits and stable financial returns. Unlike more volatile real estate sectors, the demand for affordable housing remains consistently high across all economic cycles, providing a defensive cushion during downturns. As an investment, it is characterized by durable income streams, often supported by government subsidies, which mitigate risk and ensure stable rent collections (Nuveen, 2024). This resilience makes it an attractive option for institutional investors seeking to diversify their portfolios and achieve both financial and social objectives (PREA).

Model 1: Shared Equity Homeownership

Mechanism

Shared equity is a homeownership model designed to bridge the affordability gap by creating a partnership between a homebuyer and a sponsoring entity (such as a nonprofit, public agency, or private investor). The buyer purchases a home at a below-market price, made possible by a subsidy from the sponsor. In exchange for this initial affordability, the homeowner agrees to share a portion of the home’s appreciation with the sponsor upon resale (Americorps). This structure lowers the barrier to entry while ensuring the home remains affordable for future income-eligible buyers.

Profitability & Investor Returns

This model creates a symbiotic financial relationship that benefits all parties:

- For the Homeowner: The primary benefit is access to homeownership that would otherwise be unattainable. Wealth is built through two main channels: equity gained from principal repayment on their mortgage and their contractually agreed-upon share of the home’s appreciation. A comprehensive study by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy found that the median shared equity homeowner accumulates approximately $14,000 in wealth at resale from an initial median investment of just $1,875 (Lincoln Institute, 2019). This provides a crucial financial stepping stone, enabling many to transition to traditional homeownership later.

- For the Investor/Sponsor: The financial return is realized from their share of the home’s appreciation when it is sold. Crucially, this model preserves the initial public or private subsidy. The captured appreciation is reinvested to make the home affordable for the next buyer, creating a perpetually revolving fund. This ensures long-term program sustainability and provides a continuous, albeit moderate, stream of returns, making it an attractive, low-risk proposition for impact-focused investors.

Model 2: Community Land Trusts (CLTs)

Mechanism

A Community Land Trust (CLT) is a nonprofit, community-based organization that acquires and retains ownership of land for the benefit of the community. The CLT then sells or leases the homes situated on that land to lower-income residents at an affordable price, typically through a long-term, renewable ground lease (e.g., 99 years). The key innovation is the separation of the ownership of the building from the ownership of the land. By removing the speculative cost of land from the purchase equation, CLTs dramatically lower the price of homeownership (Grounded Solutions Network).

Profitability & Investor Returns

While not designed for high-profit speculation, CLTs offer a robust model for financial stability and predictable, long-term returns for certain types of investors.

- Financial Viability: The CLT’s financial model is built on long-term sustainability rather than short-term profit. Its revenue streams include one-time developer fees, modest annual ground lease fees from homeowners, and a portion of the resale proceeds from homes sold within the trust. These funds cover administrative costs and are reinvested into acquiring more land and developing new affordable housing projects (Georgetown Climate Center, 2021).

- Investor Angle: CLTs are ideal for “impact-first” investors, including foundations, philanthropic funds, and socially responsible private investors. Capital is typically provided for initial land acquisition or construction financing, often structured as low-interest loans or patient capital. The return is not high-yield but is extremely low-risk. The investment is secured by a tangible asset (land) and insulated from market volatility due to the CLT’s resale restrictions and constant demand. This model offers a safe harbor for capital while generating profound and lasting community impact (Forbes, 2022).

Model 3: Social Impact Bonds (SIBs) for Housing

Mechanism

A Social Impact Bond is not a traditional bond but a performance-based contract that brings together the public sector, private investors, and service providers to tackle complex social problems. In the context of housing, private investors provide the upfront capital to fund a specific program—for example, providing supportive housing and services to chronically homeless individuals. A government entity agrees to repay the investors, with a financial return, but only if the program achieves predefined, measurable social outcomes. These outcomes are typically tied to cost savings for the public sector, such as reduced emergency room visits, lower incarceration rates, or decreased reliance on shelters (Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco).

Profitability & Investor Returns

The SIB model fundamentally realigns risk and reward, creating a powerful incentive for performance.

- Risk & Return Structure: The primary innovation of the SIB is shifting the financial risk of program failure from the government and taxpayers to the private investors. If the program fails to meet its targets, the investors lose their capital. If it succeeds, the government uses a portion of the verified public savings to repay the investors’ principal plus a predetermined return. This “pay-for-success” model ensures that public funds are only spent on programs that work.

- Case Study Example: The Denver Social Impact Bond, launched in 2016, provides a compelling proof of concept. The program invested $8.6 million to provide housing and support services to individuals experiencing chronic homelessness. By successfully stabilizing participants in housing, it achieved a 40% reduction in emergency medical services usage and generated a return on investment (ROI) of $2.21 for every dollar invested, demonstrating that the model can be both socially transformative and financially profitable (Number Analytics, 2025). While often focused on rental housing, the SIB framework can be adapted to fund pathways to ownership, such as financial literacy and down payment savings programs for stabilized households.

Model 4: Crowdfunding for Affordable Housing

Mechanism

Real estate crowdfunding democratizes investment by allowing a large number of individuals to pool their capital to fund housing projects. Specialized online platforms connect developers directly with a broad base of small-scale investors. This model can be used to finance the entire lifecycle of an affordable housing project, from land acquisition and construction of for-sale homes to funding down-payment assistance programs for eligible buyers (LinkedIn, 2024).

Profitability & Investor Returns

Crowdfunding offers flexibility in structuring returns and mitigates risk through transparency and diversification.

- Return Structures: Investor returns can be structured in two primary ways. In a debt-based model, investors act as lenders and receive fixed interest payments over a set term. In an equity-based model, investors become partial owners of the project and receive a share of the profits upon the sale of the homes. This flexibility allows projects to attract different types of investors with varying risk appetites.

- Risk Mitigation and Viability: Crowdfunding platforms enhance investor protection by providing detailed information on each project, including financial projections, developer track records, and market analysis. This transparency facilitates thorough due diligence. Furthermore, the model allows investors to mitigate risk by diversifying their capital across multiple smaller projects rather than concentrating it in a single large investment. For developers, a successful crowdfunding campaign can also serve as a powerful validation of the project’s market appeal, which can help secure additional, traditional financing (Turbo Crowd, 2025).

Enabling Success: The Role of Partnerships and Policy

Innovative financing models, while powerful, cannot operate in a vacuum. Their success hinges on a supportive ecosystem built upon robust cross-sector collaboration and enabling public policy. This foundational structure is essential to de-risk investments, ensure financial viability, and scale solutions to meet the immense demand for affordable housing.

Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs): The Essential Framework

Public-Private Partnerships are the cornerstone of modern affordable housing development. They create a symbiotic relationship that leverages the unique strengths of both the public and private sectors to achieve outcomes that neither could accomplish alone.

“The traditional model for housing must be reimagined so that municipalities, governments, and private capital can collaborate on this issue – achieving more together than any group could independently.” – Nuveen, FCLTGlobal Report

- The Synergy of Partnership: PPPs align the public sector’s mission—to foster housing stability, community health, and economic mobility—with the private sector’s capital, operational efficiency, and development expertise. This alignment transforms affordable housing from a social expenditure into a strategic investment in community infrastructure (Forbes, 2025).

- The Public Sector’s Role: Governments act as crucial enablers. They contribute assets and incentives that make projects financially feasible for private partners. This includes providing public land at low or no cost, offering tax incentives like the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC), granting direct subsidies, and streamlining zoning and permitting processes to reduce development costs and timelines (The World Bank, 2023).

- The Private Sector’s Role: Private developers and investors bring the necessary capital, construction management skills, and a focus on execution. They are incentivized to manage projects efficiently, control costs, and deliver high-quality housing on time and on budget, ensuring accountability and performance.

- Case Study Highlight: Bhubaneswar, India: A powerful example of a successful PPP is the affordable housing project in Bhubaneswar, India. Advised by the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the project structured a deal where a private developer was granted rights to develop a portion of public land for commercial sale. In return, the developer was required to design, finance, and construct 2,600 affordable housing units on the remaining land and transfer them to the public authority. This model leveraged private capital and expertise to deliver a massive number of affordable homes at minimal direct cost to the government, creating a replicable framework for other emerging markets (IFC Project Brief).

Supportive Government Policies

Beyond the partnership framework, specific government policies are essential for creating a favorable investment climate and directly assisting homebuyers.

- Financial Incentives for Development: Programs like the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) are the single largest source of financing for affordable rental housing in the U.S. and a critical tool for making project finances viable for investors (Shelterforce, 2023). Similar tax abatements, fee waivers, and direct capital subsidies are vital for reducing project costs and de-risking investments, thereby attracting the private capital needed for development.

- Zoning and Land Use Reform: Outdated and restrictive zoning is a primary bottleneck for supply. Governments must enact reforms that permit greater housing density, allow for a variety of housing types (e.g., “missing middle” housing), and establish faster, more predictable permitting processes. These changes are fundamental to increasing the supply of buildable land and lowering the cost of construction for affordable projects.

- Down Payment Assistance (DPA) Programs: Even with innovative financing that lowers a home’s price, the upfront down payment remains a major hurdle. Government-funded DPA programs, often structured as grants or forgivable loans, can be layered on top of models like shared equity or CLTs. This provides the final piece of the puzzle, enabling credit-worthy, low-income families to clear the last barrier to homeownership.

Conclusion: Building a Future of Accessible and Profitable Home Ownership

The challenge of bridging the gap between affordable home ownership and investor profitability is one of the defining economic and social issues of our time. The analysis demonstrates that this is not an insurmountable dilemma but one that requires a decisive shift away from traditional, one-size-fits-all approaches. The solution is not a single silver bullet but a sophisticated, multi-pronged strategy that aligns public purpose with private incentives.

The innovative investment models explored—Shared Equity Homeownership, Community Land Trusts (CLTs), Social Impact Bonds (SIBs), and Crowdfunding—offer a powerful toolkit. Each presents a unique value proposition, balancing risk, return, and social impact in different ways. Shared equity and CLTs directly lower the cost of entry and ensure long-term affordability, providing stable, community-focused returns. SIBs and crowdfunding, in turn, introduce new sources of capital and performance-based discipline, democratizing investment and funding pathways to financial stability.

Key Takeaways

- The housing crisis is driven by a combination of economic pressures on buyers, severe supply shortages, and systemic barriers.

- Innovative models like Shared Equity, CLTs, SIBs, and Crowdfunding can make homeownership accessible while offering viable returns for investors.

- These models succeed by lowering entry costs, preserving subsidies, linking returns to social outcomes, or democratizing investment.

- Success is not possible without a supportive ecosystem of Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) and enabling government policies (e.g., tax incentives, zoning reform).

Ultimately, the path forward lies in the strategic integration of these elements. The future of housing affordability hinges on the ability of policymakers, developers, and investors to collaborate effectively. It requires deploying these innovative financial instruments not in isolation, but as part of a cohesive strategy, underpinned by strong public-private partnerships and intelligent, forward-thinking government policy. By doing so, we can construct a future where the security of home ownership is within reach for more families, and where investing in that future is a profitable and purposeful endeavor for all.